Know the Structure and Key Stakeholders

A good cybersecurity manager must understand both the organisational structure and the power structure of the organisation they work in. This is essential. If the cybersecurity manager doesn’t know who makes the final decisions, who controls the money, and who the key influencers are, it will be difficult to be effective in the cybersecurity manager role.

Study the Org Chart

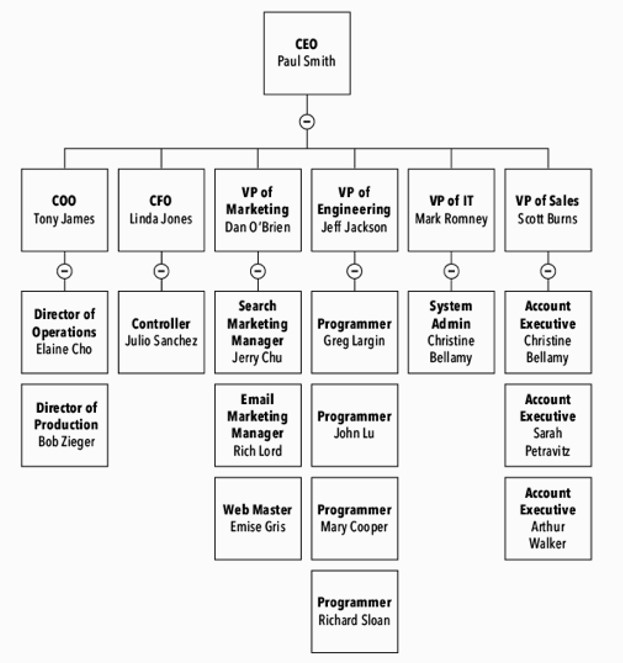

Studying the organisational chart of the company is the quickest way to get the lay of the land, figure out who’s in charge, and discover who reports to whom.

Looking at the org chart, the cybersecurity manager can see if the company is structured in a line or a matrix. In a line organisation, depicted by the typical upside-down tree chart, the hierarchy is clear. Key executives are listed at the top of the chart and department heads below them, then the managers, and so on. In this scheme, each owner has a budget, and you can go straight to the owner with requests. In a line organisation, the cybersecurity manager should talk with each owner about how security is relevant to them and their department.

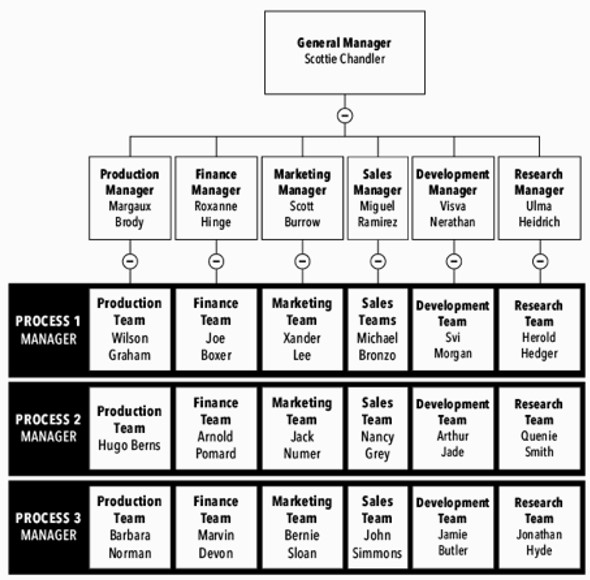

In a matrix organisation, however, the landscape is a bit different. Here, employees are divided into teams by projects, which gives workers multiple reporting relationships, for example to a functional manager and a project manager. In this scheme, a quality manager or product owner might work with people on every line, making for some complex relationships. What the cybersecurity manager needs to understand is that this manager or owner is not the boss with the budget. In a matrix, the cybersecurity manager must negotiate with people in all of the business lines.

In either type of organisation, the cybersecurity manager’s goal is to find out about any security concerns and learn who is responsible for those areas. It’s not always clear. Many supervisors, though they are responsible for monitoring safety and security, don’t even know where to find cybersecurity procedures. They may not know what to check when they hire people, or they might forget to collect computers when someone is fired. Some don’t feel security is their business—production managers figure they handle production plans, not security—until the day there is a problem, and they realise it is their responsibility.

For example, we worked with a government organisation in Finland where an older lady, who had served as the cybersecurity manager, was preparing to retire. As she prepared to hand over the reins, it became clear she didn’t have a clue about the organisational structure or even where to report security issues.

After a day or two working with this lady, studying the organisation, and having discussions with her and her colleagues, it was actually quite clear who was making decisions in the company and what kind of management structure was needed for security. This woman could have studied the org chart and discovered who she needed to talk to. She had just never bothered to do it.

Finding out about the decision-making process in an organisation is crucial. Without a solid grasp of organisational structure and decision-making, the cybersecurity manager will struggle to get anything accomplished. The organisational chart is a helpful starting point, but it’s equally important to study process flow charts and understand how things are produced and communicated.

With that in mind, cybersecurity managers also need to be aware that all the information about who has power and influence in any organisation is not necessarily on the official org chart. Often, in bigger companies especially, virtual teams have authority to decide on certain matters, especially regarding security. Those teams aren’t usually visible in the chart. Many influencers may not appear on the chart at all, so cybersecurity managers have to talk to the people in charge, ask them how decisions are made, and find out who makes the final decision.

Think Big

The larger the company, the more challenging it is to communicate security issues and to get acceptance on policy. In a smaller company, cybersecurity managers can always go right to the head of the company to get a yes or no. That’s easy. But when working with a bigger, more complex organisation, it can be harder to discern the existing roles and power structures.

For example, firewall management isn’t just about managing a device; it’s about managing people. The firewall is centralised and everyone goes through it. Employees working from home, for instance, have to be able to access internal applications held by different business units, and they need a way to do it securely. Firewall rules need to allow access while remaining secure.

There may also be policies that get created in different, cross-functional bodies. Geography may be a factor—say a Singapore company’s IT or management is in another country and needs permission to do something in Singapore. Seeking permission causes delays the organisation can’t afford because the problem is real and happening now. Hackers are not going to wait for permission from the US or Hong Kong.

Multinational companies have to figure out how to address this problem. Are they going to write policy, so it applies to all countries similarly? Do they want to leave it on a high level, so it’s floating in the ivory tower of the home office? Or will they start making a different policy for each country? Every decision, whether centralising security decision-making power in the main office, or spreading it out to each country’s local organisations, or working out a hybrid model, will have significant ramifications.

Understanding the differences between countries and organisations and their managers is crucial for cybersecurity managers because they need to know who holds decision-making power. For example, a company in the US with offices in Bangkok might not be very well managed in Thailand. Let’s say the Bangkok office is missing a CEO at the moment, or maybe it has financial problems or sales problems. In that case, it would be almost impossible to push for the security issues from HQ because it’s not generally managed well there.

Subscribe To Our Newsletter

Get the latest intelligence and trends in the cyber security industry.

Outsourcing

Another layer of the security landscape is outsourcing. Security isn’t always handled in-house. Many companies today are outsourcing their IT, cybersecurity, and development functions. That makes a big difference in the role of a cybersecurity manager. If IT is outsourced, there’s often an extra layer of formality between the cybersecurity manager and upper management, and it’s difficult to get any support from the outside contractor beyond the scope of the contract or the frame of the service level agreement.

Identify the Influencers

With so many people’s input to consider, the cybersecurity manager has to make some decisions about who to listen to first. The dog that barks the loudest is not usually the most dangerous one. In this case, the analogy means that some of the most powerful people in any organisation may not have any official role in the management structure. These are usually long-time employees who get things done and influence decisions, even though their title might be administrative assistant or office manager. Most companies have these influencers, people who are superconnected to the highest-level executives and know them all well. These influencers are important people to identify.

It might be difficult to identify these roles before spending considerable time in the office. Getting to know people is crucial, and that takes time. Sometimes, a cybersecurity manager will get lucky and get to work with a very influential person who supports cybersecurity and supports the cybersecurity manager’s efforts. For example, we know a multinational company in Europe that had a fairly large IT budget—in the tens of millions. It just so happened that a lot of key decisions were made in the application development steering committee. The steering committee didn’t appear anywhere on the org chart, but that is where the decisions were made.

Overlooked Influencers

Sooner or later, someone in your company will ask, “Do you know Martha? Martha knows everyone!” If you don’t know your company’s “Martha” yet, get to know her. Martha might be an executive assistant, a secretary, or a human resources manager. No matter her official position, she knows what’s going on and can get your ideas heard.

When a cybersecurity manager is building an expensive application for a business purpose and has the ear of the committee that makes decisions about those applications, they can control a fairly large budget. The cybersecurity manager in that scenario better be present in those committee meetings to be heard and to find out how the company is led and what the foundational issues are.

cybersecurity managers may be surprised to discover what influences a company’s decisions. Even a past event can be an influencer to a company. This includes any major crises in the past—such as a past cyberattack, a failure in compliance, a bribery scandal, or any negative story in the media. After events like that, security will be more important than ever, even if the scandal wasn’t directly related to security.

Know the Stakeholders

Every organisation has multiple stakeholders, and the cybersecurity manager would be wise to identify them and get to know them, because each type of stakeholder can pose a unique challenge. At some point, the cybersecurity manager can expect to navigate some kind of fight between the manager and the compliance folks, for instance, or between the manager and the risk folks. Some challenges are predictable, and the cybersecurity manager can prepare for and manage those. In this section, we’ll review some of the most common stakeholder challenges.

Aligning with Compliance-Driven Stakeholders

Compliance means every company in the same field has to solve the same requirements. These tasks come from industry standards, or even laws, and are imposed from outside the organisation. Companies have to address them even if they don’t seem to make any sense. Fortunately, companies do have some choices about the solution and its implementation. For instance, if user access management is a requirement in a standard, you have to meet it, but you can choose how to do it, whether through policy, training, installing new technologies, or other means.

It’s easy to lose sight of this relative flexibility because people who are experts in compliance tend to take things very literally. If compliance says to open the window, you must open the window, even if there’s already a massive hole in the wall or an open door one metre from the window. Nobody gets bonus points for going above and beyond in compliance. They just need to tick the box.

And yet, compliance is unavoidable because if companies are non-compliant with regulations, they run a risk of eventually losing their licence to operate in their field of business. The process may take a while—companies usually get some time to respond and try to fix the issue. On the other hand, public response can be immediate; airlines, for example, can’t skip their safety check—even if they would save a ton of money—because they would get very bad press and go out of business.

Compliance is such a challenge for business owners because regulators don’t care about value. Most compliance officers don’t even talk about cost-benefit analysis or return on investments; they might not even know what that means. (Although a deeper look often reveals the return is in the regulator’s interest.)

From a business perspective, compliance gives no competitive advantage because everyone is in the same boat. Compliance almost always destroys stakeholder value within the company. The business-minded cybersecurity manager will take compliance with a grain of salt and try to implement it, so they can stay in business while doing minimal damage to the bottom line.

The irony is that all the compliance in the world doesn’t always lower your risks. Complying with all the regulatory standards doesn’t make a company secure. You can buy a scanning tool for your e-commerce site and run it four times a year—you’ll be compliant. You won’t get fined. But you may not be any more secure than before. Still, if a CEO has to make a choice between compliance and security, which one should he make? There’s really no debate—he has to always choose compliance.

Aligning with Risk-Driven Stakeholders

Risk experts have a very different mindset from compliance officers. Risk experts believe that risks are inherent in everything, so it’s their mission to list and assess them all. Even if there seems to be an unlimited amount of risk in a given industry, their job is to attempt to analyse it. They want to be helpful. They try to understand the business. Risk experts are often much easier to talk to than compliance officers.

Risk people are numbers people who calculate probabilities. Risk management has its roots in insurance, where most risks are quantifiable. Insurance companies look for the magic formula that makes the most money, and they spend years creating it. If they get the life insurance formula right, they make better profits than their competitors. They don’t even start insuring something that they can’t calculate. Unfortunately, finding a formula is seldom straightforward. Most of the risks in the world are hard to quantify.

Know the difference between compliance and security risks. Don’t ignore either.

The big problem for companies is that their risk expert is usually overwhelmed by the many people who come to them with their risks. They can only manage a few of the biggest ones, leaving the rest behind. Large organisations with thousands of employees might solve this problem by hiring multiple risk managers with a variety of titles, like Senior Risk Manager or Director of Risk Management. They might even benefit from creating a risk management team. In some industries, specialised roles may be dedicated to different areas; for instance, people with the title of Risk Manager may have specialised functions that deal with fraud or assessing the credibility of cardholders before giving them limits. In those roles, they’re dealing with one particular type of risk.

While compliance people want you to tick the box, risk management people would rather see you run penetration testing or some kind of analysis to find out if the application is actually secure or not because they want to mitigate the risk. They also want to maximise opportunities. For example, building in strong security while you’re creating a new internet trading platform does a lot more than just prevent losses—it gives you the opportunity to be in business. Without it, customers will not trust you. By implementing it, you not only prevent losses, you enable the whole business.

Aligning with Business-Driven Stakeholders

Business people can push back on both the compliance and risk experts. They’re interested in how fast things can move and how much profit they can make. Once they’ve developed a new system, they want to know: Is it safe to put online now or not? How long will it take to fix it? How do they avoid delays? Business is always about profit, and it always comes with a risk, so a cybersecurity manager who understands both can help make the best decisions.

Business people are goal-oriented; they don’t want to hear about problems. The last thing they want to hear is compliance saying, “You didn’t have this one policy written up and accepted by certain boards.” Business people are always trying to accomplish more, and it looks to them like compliance sets obstacles and limits just to reign them in.

Balancing Stakeholder Interests

Each category of stakeholders comes with its own deadlines and pressures, and they often conflict. If there’s a potential security problem, for example, the compliance people don’t care how long it takes to address it, while the risk people try to figure out the probability that someone will hack it before a patch is in place. Business people, on the other hand, might think it’s not a big deal at all. They’re apt to say, “If we put it online now, we’re going to make this much profit, so it doesn’t matter if there’s a small loss.”

The cybersecurity manager in any organisation will have to interact with a variety of stakeholders like this, each with their own set of wants and needs. The art of cybersecurity manager is in trying to find the right balance between these three groups.